Alice Ford signs as Big Al. More than her artistic persona it is an artistic statement against individualism and prejudice. A mind opener to embrace mystery, artistic freedom, and a multidisciplinary work force. Emergent, visionary, observant Big Al’s art is in full resonance with its contemporaneity and engaged in a deep critical thinking. Originally from Fremantle, Big Al is moving down to Margaret River to make this place her home and artistic hub.

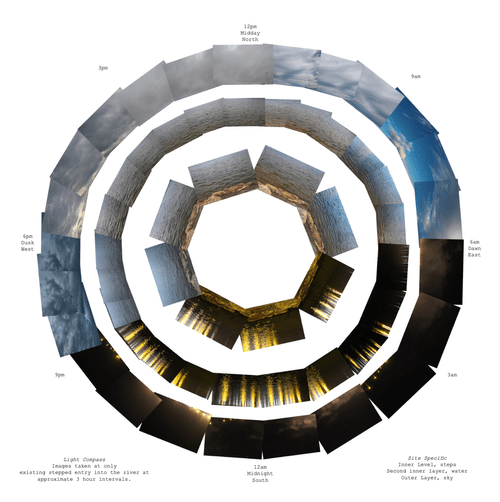

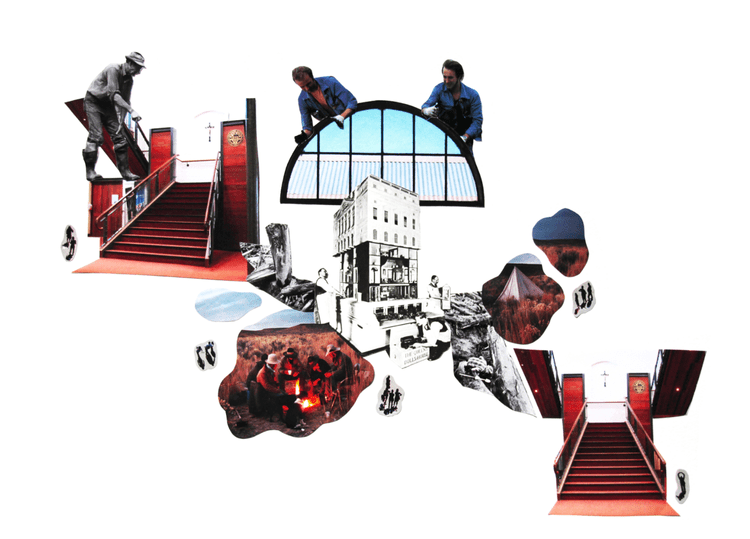

Big Al, The Derbal Yerrigan Site Compass (from Notre Dame design studio),2016. Digital collage from site photographs. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

Big Al first grabbed our attention when we came across her graphic collages – lively and humorous. It didn’t stop there. Big Al’s ever-growing collection of materials and different mediums enhanced her practice to another level of storytelling.

Ultimately, her experiences abroad in field work and environmental designing got us intrigued.

Welcome to Margaret River. Is Big Al your pseudonym?

Yes. I came up with the name a few years ago and then didn’t have the courage to call myself that for a while. The name is who “I would like to be”. I’m making my own art and I think when I feel that I can’t do something I say, “What would Big Al do?”, and that is how I become that

artist. I’ve noticed now that I’ve been introducing myself as Big Al instead of Alice which makes me feel big.

And it doesn’t have a gender?

Yes – no gender. It is a pseudonym.

How do people react to that?

Some people make fun of it.

Why?

Because they think “Who are you to call yourself that?”, and they find it strange. But that’s my name and I love it! Instead of asking “What Big Al would do?”, I ask myself “What would my eight-year-old version say?” And the eight-year-old version wouldn’t care what people think.

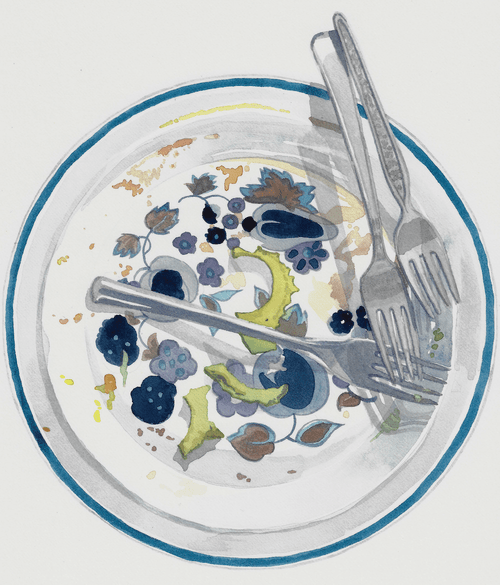

Big Al, Avocado Crusts,2016, Gouache painting on watercolor paper. Image credits © Copyright Big Al 2025.

You finished your architectural degree a few years ago. Does your drawing skill and technique come from your architectural practice or is it a separate practice?

When I was a student, one of my favorite teachers said that you must always carry a moleskin with you, and that was part of our assessment. They would look into your journal at the end of the assignment. So, I bought one for my art and then another for my architectural work, I always had two. When I went to Japan it became one. The collages as well, I started doing them with no purpose, just because I simply loved doing it, they drifted in and out, and then would occasionally puncture different architectural assignments. Now I know both creative practices can’t be separated.

But I’m still experimenting with how I can bring this into my formal architectural work.

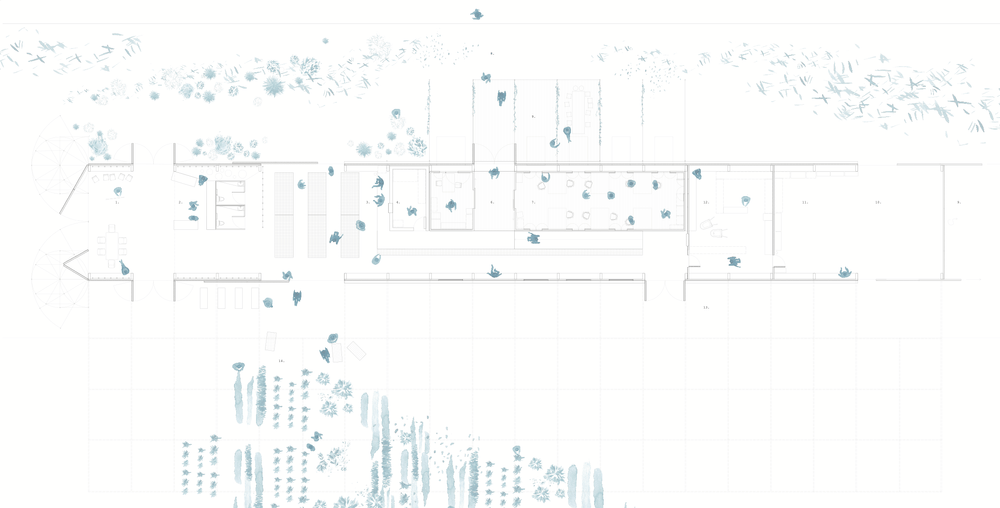

Big Al, The Legacy of APACE Nursery – designing for 100 flooded future, 2020, Digital drawing and digital collage ink painting. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

When looking at your practice, we see that you explore different mediums and different subjects. Do you think it is important for an artist to have their own style or it is more interesting to be open and more versatile?

I think if you had asked me that question two years ago, I would have said stick to one thing. But now I think the opposite. Don’t have limitations about what you’re making. It is important to think about the concept and what you’re trying to say and ask yourself what is the best medium to do that.

I had great teachers who told me “You need to push that!”. What are the different drawing techniques you can do, collage, video. I found a book at the time with advice for emerging artists. I was reading it just looking for any sort of guidance during that time because I was in full experiment mode, and their advice for young artists was to not to stop following the “style” that people know of you, keep doing all the other things. You never know when they will loop back into what you’re doing now.

Is there a particular philosophy you’re trying to embody through your work?

I’m really interested in people and the events that connect to landscape and buildings. That is probably the architecture student in me. I’m fascinated with people and buildings as ecological engines. Especially in architecture, nature is outside, and buildings are inside. I’m interested in how mixing those could change our lived experiences and daily realities.

The Southwest really influenced my conceptual view. Here you have such an abundance of environmental artists.

We found interesting that you define yourself as an environmental designer.

I could expand on that. I have noticed in the last few years that when people ask “Are you an architecture person? An artist person?”. It is like “Give me a title so I can figure you out”. I noticed that I would change my title depending on who that person was so that they would listen to me. I would say I was an environmental designer if I was in a group. I think a lot of people who work across many disciplines do this. However, I have decided I am happy to say artist now!

Does it have to do with the word Artist?

Yes, it does. I think artists get an unfair rap. Recently I had people saying, “Oh well, you’re just having fun all the time, aren’t you?” or flamboyant, you go with the wind. We have a work value culture: the harder you work the more value you have, so I had to deconstruct all that over the

last two years. I have done a lot of reading to see these patterns around the word “work”.

Culturally in Australia you are viewed kind of lazy until you become a genius and then everyone goes “Wow, you’re amazing!”. But who decides that you’re a genius? Or when are you good enough to pass that test? They don’t think you’re serious or contemplate serious issues, or that your work can be of a surface value only for aesthetic reasons. Aesthetic art does have a value, and we need that in our lives too. That is joy. You can’t just have a functionalist existence!

Big Al, Avocado Crusts, 2022. Gouache painting on watercolor paper. Image credits ©Copyright Big AL 2025.

Who do you look up to as an inspiration?

Miranda July is a huge one, she is one of my heroes. I was reading about her work, and she spoke about her recurring theme – loneliness. You can see that infiltrating everything, but it is not direct either, which I think is beautiful. Shaun Tan is another big inspiration since I was tiny. His books were my most prized possessions, and I have one of his prints which was a gift.

I’ve started falling in love more and more with filmmakers. Hayao Miyazaki’s film The Boy and The Heron is fantastic, and it is meant to be his last movie. I went to his museum in Tokyo when I was over there, and it just blew my mind because they are paintings – every single frame is a

painting and it is about making them move and tell the story.

Agnes Denes is another great influence. She was one of the first to do urban installation environmental artworks. I really love her work. The more architectural sort of way she draws patterns, I find that fascinating. I love her ideas, and her concept of time is deep compared to other environmental artworks. Her works will live for decades or hundreds of years. We need more of that.

Do you ever come into conflict with yourself about your work?

Yes, you question a lot, you go back and forth. I found this questioning process scary at first. I found not having a framework quite frightening as it made me freeze, I didn’t know if it was the right move. But now it has become one of my favorite things starting each day: the limitlessness of creative practice and that questioning process.

You were in that space two years ago. Then the residency in Japan came up. Did the residency solve questions, or did it give you an escape from them?

I thought that was such a privilege to be able to do that and so precious, it helped me answer all the questions like “How am I going to structure my day?”,” What works for me?”, and let me ask all the ones that I hadn’t been asking myself like “What do I really want to make?” and not “What should I make?”. There is that risk of becoming a marketeer or being in a business that makes it really hard to manage these two questions.

Your job as an artist is also a business and you can’t forget about that.

I was 18 years old when I decided to share my artwork on Instagram. That was eight years ago, and that is how people knew that I was making art. But then after a few years, I was making art for Instagram, and not for me anymore. It is a slippery slope, I was all business, no soul. And now I’ve gone back. Another loop. If you stay true to yourself that part will come as well, and you will start making things that feel authentic, true, and honest and people will go “Oh, I like that!”. You’re interested in what you want to show. I read Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert (1), and Women Who Run with the Wolves (2). I realized I needed to do work that allowed me to have freedom and not just doing work for clients. Now that I have another income stream this gives me more freedom to make things without the pressure of knowing whether I will be able to pay rent this week.

You can do both. Many artists do two parallel things.

Yes, I started to do parallel work, and I love it.

Big Al, The Tennis Players, 2018, Analogue collage and dried flowers. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

Do you ever feel the need to justify your work?

Less and less every day. That comes with any new skill which takes practice and repetition. When I go to my studio, I go “I can’t believe this is my job!”. When I launched my Big Al website, and when I started to call myself Big Al, the justification stopped.

Laura McKendry, an English artist, and educator said, “The aesthetics of the natural world are worth making time for.” Do you agree with this statement?

Yes. It is the inspiration. That is where it starts. When I find artists or works that aren’t connected to nature, I find it hard to connect, but that makes me think differently though and that other people have different inspiration. For me it is one hundred percent worth making time for and I

can’t see a negative. We are part of it, and I find it strange to separate us from the natural world.

“As more people move into cities, we are pushing the wilderness further and further away, the more I want to bring it in. Beauty is a way to access that counterpoint for despair.”

Why is it important to find beauty in Nature?

Growing up, when I would see beauty in Nature there would be these odd moments of stillness – I think a lot of people feel that way. I grew up in the city, in Perth. I loved growing up there. When I think of my favorite things as a child, a lot of them were outside, weren’t inside.

As more people move into cities, we are pushing the wilderness further and further away, the more I want to bring it in. Beauty is a way to access that counterpoint for despair.

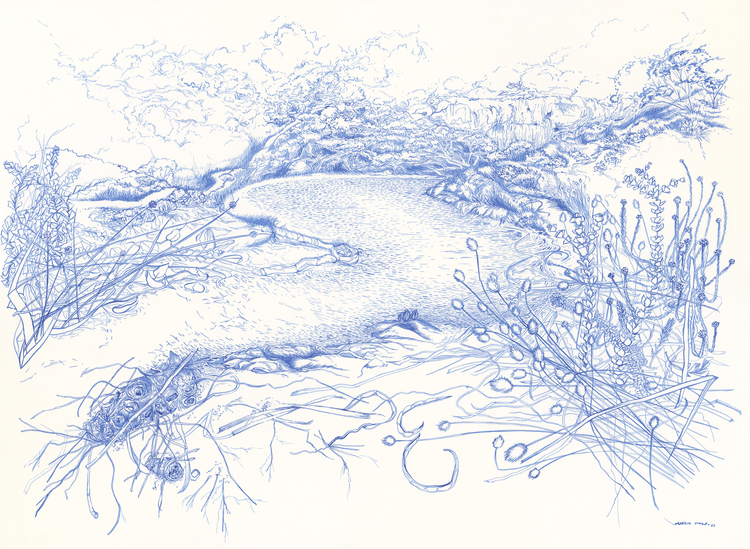

Big Al, Blue Bilya, 2022, Ink on watercolor paper.© Copyright Big Al 2025.

“My artwork isn’t successful unless you can join in.” This is a quote from Australian artist Anna Wili Highfield. Do you think about the participation of the audience when you’re making a new artwork or art project?

Once I went to talk to Year Threes about my career as an artist, and one of the students asked me why my collages were so funny. I looked at the board where the collage was and had a big laugh! I hadn’t thought of that! Being funny to experience. My works use comedy to interact with the subject matter. I can’t connect without comedy or familiarity. Comedy and despair are so interlinked when you push through something that it is so uncomfortable, you kind of laugh as there is nothing else you can do. There is this filmmaker called Amelia Ulman who made a beautiful movie called El Planeta (3) which I really recommend. There is also a book by Timothy Morton All Art is Ecological (4) where he explores how absurdity, surrealism and interacting through comedy can still communicate moving through the despair of the situation.

Much of your work and art exhibitions have been centered in Fremantle where you were based before moving down south. How is Fremantle for an artist?

Fremantle (Walyalup) is a big reason why I even thought being an artist was a career option. So many artists live there. My first job was right next to Mojo’s Bar and that’s how I started to meet so many musicians. At that time, I was doing a lot of artworks for musicians

album covers and posters.

And with a good artistic network?

Oh yes. You have a friend who knows a friend of a friend and that’s how you connect, and it is so important. Now that I moved down here many of my questions are about how to find artistic communities in a rural landscape, as I want to live here and make it my home. But I’m still going to be travelling up to Fremantle for my parallel work. I don’t want to lose that network either as it has been my network since I was 16.

We also noticed that you’ve created artworks which part of the percentage of their sales have been donated towards charity organizations or nature conservation. Is this a form of artistic activism?

Yes, I donate to organizations that I passionately support or love what they’re doing. Also being an artist is to question your value of money. One of my favorite books The Art of Frugal Hedonism, Annie Raser-Rowland with Adam Grubb (5) talks about when you give a portion of what you have, it makes you feel you can give, no matter how much you earn. Instead of this feeling that I must save, save, save. I have everything I need. I can always take a little bit and give elsewhere.

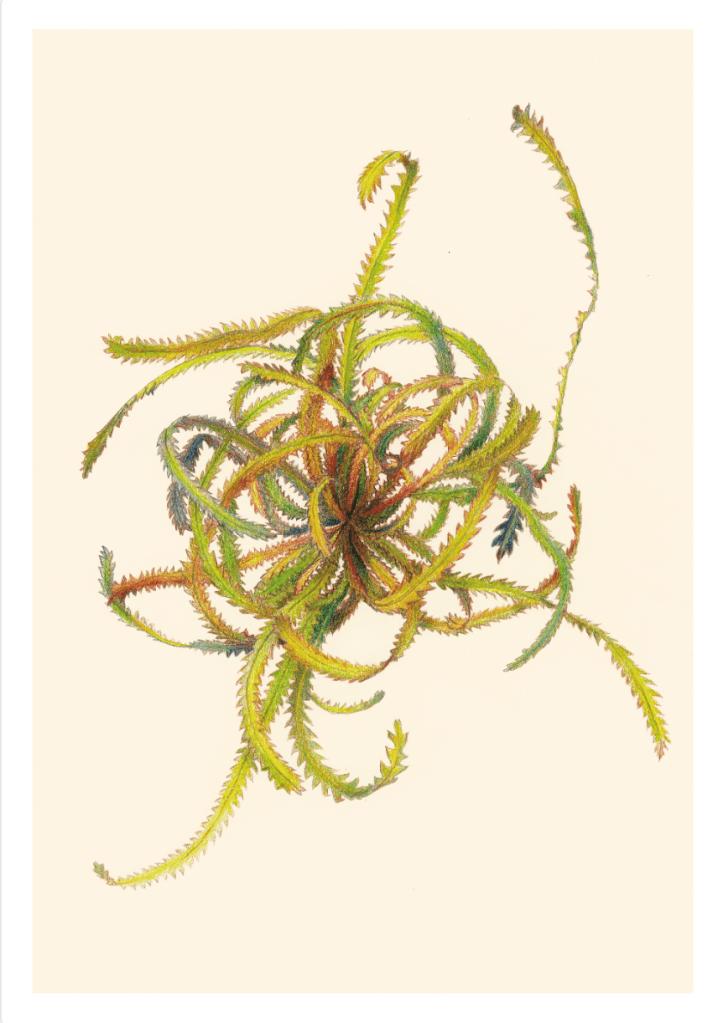

Big Al, Unfurling Banksia, 2021, Original work polycolor pencil on watercolor paper. Published in 2023 in the Forests Atlas. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025

And it brings more awareness about the organization you’re supporting at the time.

Especially APACE, the native plant nursery in North Fremantle not many people know about them. They just keep steadily doing their work without having big banners everywhere. They’re a hidden beautiful organization in North Fremantle.

You have participated in a few artists residencies, both in Australia and overseas. How important were these to consolidate your artistic path?

Since I was 18, I had to have a goal – what was the thing I wanted to do that I haven’t done yet?

My art website, an art exhibition. Each year was always one thing. A couple of years ago I decided I wanted to do an artist residency, and it seemed perfect timing. I couldn’t tell you how many I applied to. It is a long and involved process, and one day you’ll receive mail saying that you are one of 550 and they can’t give feedback as there were so many people.

The best thing about these residencies was living with other artist’s full time. The Donnelly River artist residency we were five, and we all had a different medium, it was just chaos, wonderful and strange. When I went to Japan, some came from Paris, Vienna, New York, and Santa Cruz, it was such a melting pot, everyone was doing different projects with different mediums, and we had to live together for a month!

The work and artist residency in Itoya, Japan and the field farming works you have done – they became experimental artistic projects. What was the main idea behind them?

When I applied to go to live and work in Japan, I went on a holiday visa and didn’t have a lot of money. One of the tips I got from The Art of Frugal Hedonism was to work away woofing. I worked and lived on farms on my journey from Tokyo to Itoya where I had the artist residency. I started to think about farming as a space that connects to landscape and buildings. I became obsessed. It started as work to get money and then became the main drive of the whole trip. This is agriculture, and how you maintain biodiversity, through agriculture, architecture, and ecologic engines. A lot of the people that I met working on the farms were also artists. I realized that being an artist is like farming – working all the time, planting, then waiting, waiting and then you harvest. Then again.

Two of the artists I met were Aiko Owada and Makita Sayaka. They were also working in farms as it was so similar to making art, the manual labor so tactile. Aiko is also a lecturer at Zokei University in Tokyo, and her artworks are inspired by fieldwork. She told me that there was

no difference between her artwork and her fieldwork. That is how we started to work together on this project.

Big Al, Farming Futures – Japan, 2022, Gouache, analogue collage, printed 35mm film on washi paper. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

The same with Hatake Seed Work (6) – you defined it as an artistic experimental field work project. Is there a suggestion of an alternative artistic practice?

I’m really interested in Masanobu Fukuoka and his ideas about natural farming which is to give nature as much control as you can. We went to Aiko’s field, and we were experimenting with his methods. Fukuoka’s book reads like an instruction manual, but also has chapters of philosophy and poetry. We wanted to experiment with what she needed to plant in this way,

which involved scattering seeds and using weeds instead of pulling them out. Then we staked out, in this fluorescent pink tape the area and then kept in contact about how it developed.

The field artwork is the performance. Photographing that performance, monitoring how that grew, that was how the field work became the artwork. It was a conversation between me, Aiko, Makita and the field. I think the time in Japan and meeting all these incredible women was

about broadening my idea of what art is.

Recently you participated in the publication of Forests Atlas (7) with one night exhibition at the Moores Building in Fremantle. How did this invitation come about?

When I was a student, I had a visiting lecturer, Daniel Jan Martin. He asked if I wanted to help him with his PHD and that was my first work assisting him and collaborating in one of his case studies. Since then, we have been collaborating for three years now a few projects. When he was going to make this book with WA Forest Alliance he didn’t want only maps, but many ways of showing the forests down south. Instead of seeing this place only from the sky, its understanding became broader through different perspectives. The book became a conversation between Noel Nannup, Clancy Martin, Nansen Robb, Mariela Espino Zuppa and me. We thought to launch and that’s how the Moores Building got involved as a venue. We worked together with WA Forest Alliance to present this one-night exhibition book launch, a happening.

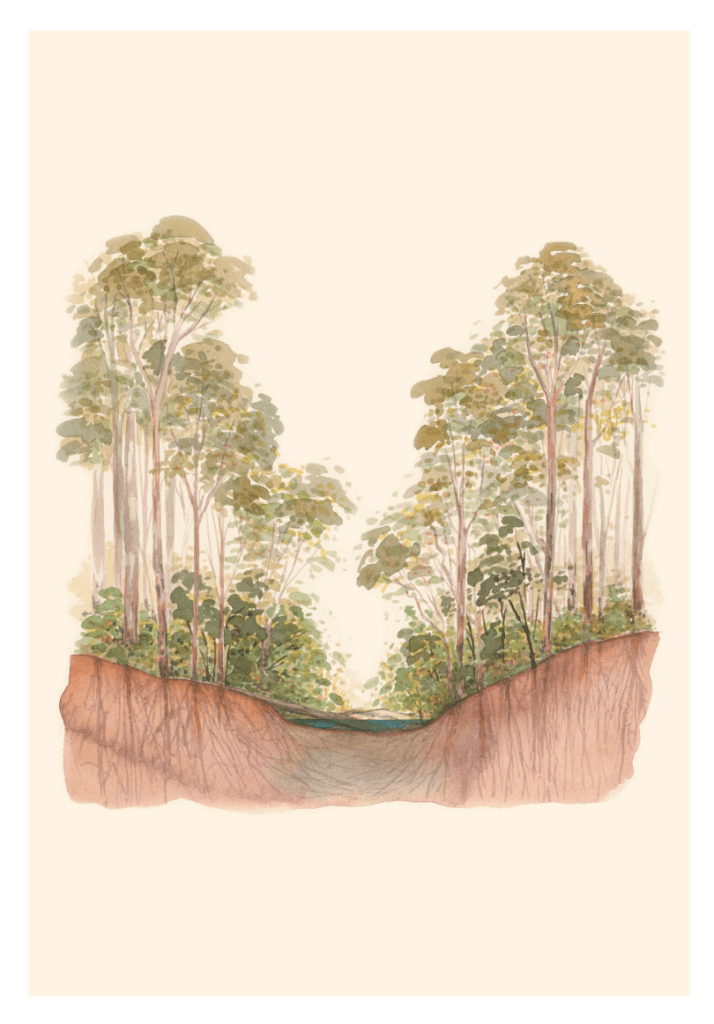

Big Al, Deep-rooted, 2022, Original gouache painting on watercolor paper. Published in 2023 in the Forest Atlas. ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

What do you take from collaborating with other artists?

Everything. Even the work I do with my printer Joe in Fremantle is a collaboration. He is an artist too. How the work is produced, how it is communicated that becomes a collaboration in itself.

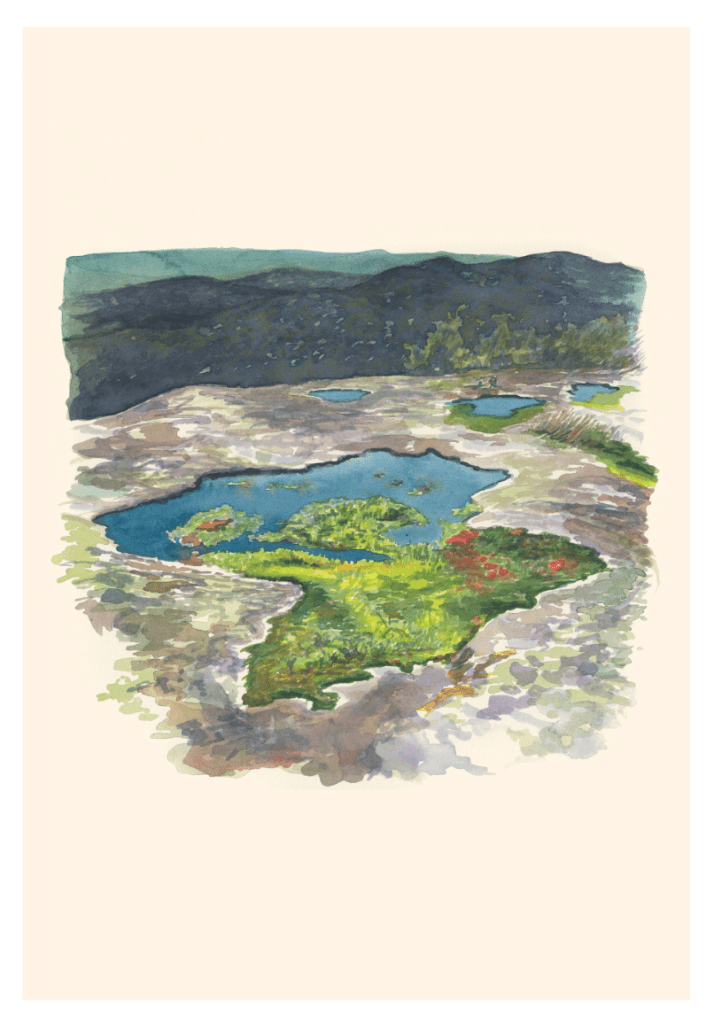

Big Al, A gnamma perspective, 2022, Original gouache painting on watercolor paper. Published in 2023 in the Forests Atlas. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

Art and feminism. According to studies, since the 1971 Linda Nochlin’s essay about women artists (Why have there been no Great Women Artists?(8)), more work made by women artists have been recognized as important. How does this impact female artists of your generation?

It is brilliant that work by women artists is being recognized (finally). They always were. As a young woman, I feel like there is a new awareness that our voices haven’t been heard for a long time. A long time indeed. There are new seats at the table so to say. I am grateful for the work my mother and grandmother and all the generations did before to get me this seat. However, that isn’t to say that everyone is all about listening now.

I have had older men rudely ignore me as I walk into spaces, or only introducing themselves to the other men in the room before a meeting. I’ve had people say in response when I told them I’m designing a house, “What? You?” like they can’t believe a woman could do something so momentous.

Honestly.

In saying this, I am working regularly with two male colleagues on an environmental design team. The projects we work on are almost always with like-minded who do recognize female artists voices as worthy — and important. I have always felt deeply respected during these projects as an equal and during our collaborations. All the work by women before me has made that happen.

What would be a dream project for you to work?

It can change. Now, I’m doing the first one which is designing a house. In parallel to that is working on a short film. I’m almost finished the script and the storyboard and am slowly accumulating people who are experts in making costumes, props, filming, and editing. I would like to make a short film where I can experiment with animation and painting using frames like I saw in the Tokyo Museum (cel-based animation).

One last question which brings us to the beginning to how we got interested in your work – your graphic collages. How do you look back to those now?

I look back at them and they are true. Some of my first works that were a bit of Big Al, all these things that shifted and got lost for a bit, now they are coming back. That’s how I think of them, like a cycle.

Big Al, The Wheat Chapel (from Notre Dame design studio), 2020, Analogue collage. Image credits ©Copyright Big Al 2025.

Thank you, Big Al.

Jenny Potts Barr & Daniela Palitos

1 Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic, 2015.

2 Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Women Who Run with the Wolves, 2008.

3 Amalia Ulman, El Planeta, 2021.

4 Timothy Morton, All art is Ecological, 2021.

5 Annie Raser-Rowland & Adam Grubb, The Art of Frugal Hedonism – A guide to spending less while enjoying everything more, 2016.

6 Hatake Seed Works, thatsbigal.com

7 Forests Atlas, Ed. by Daniel Jan Martin, 2023.

8.Linda Nochlin’s Why have there been no Great Women Artists?, 1971.

©All images in display Copyright reserved to Big Al aka Alice Ford.

GREAT article. Loved reading this one, and meeting Big Al.

Oh, thank you so much Fiona!

Really appreciate your feedback!